Fishing for Hooks: A Therapeutic Misadventure

It’s two o’clock in the morning. You’re busy charting at your computer when you see a stretcher rolling by. The medics inform you- “this is a 55-year-old male coming in for fishhook ingestion,” and hand you a stack of papers. You eyeball the patient. He looks like an average middle-aged Caucasian male in no acute distress. You note that he’s sitting up on the stretcher, with his right hand wrapped around his trachea. He’s actively talking in full, clear sentences to the nurses, and you get the following vitals on the monitor:

Temp: 97.7, HR: 71, BP: 125/79, RR: 15, SpO2: 97% on room air.

As the nurses are busy changing him into a gown and inserting IVs, you look through the stack of papers and read the following HPI:

The patient is a 55-year-old male with no significant past medical history presenting from urgent care with concern for three-pronged fishhook ingestion. Earlier that afternoon, the patient was driving from one of his usual fishing trips when he decided to reach into his glove compartment and grab his daily dose of pre-bagged vitamins. Unbeknownst to him, one of his fishhooks took a miscalculated adventure and fell into his vitamin bag. Without looking, the patient reached into the bag, grabbed the vitamins and fishhook, and swallowed them whole. Immediately after, he had a sharp pain in the back of his throat that was made worse on swallowing. Thinking he had a vitamin stuck in the back of his throat, he tried several methods to dislodge the object, including inducing emesis three times, trying to manipulate the object using his fingers, and eating several clementines in the hopes of forcing the object down his esophagus. He eventually realized that one of his fishing hooks was missing. After several hours of futile efforts, he decided to go to urgent care, who immediately sent him to your hospital.

Diagnosis and management:

Foreign body esophageal ingestions are rare in adults compared to children and are accidental in 95% of cases. They are primarily related to food (bones, chicken, toothpicks), and typically pass without intervention. Endoscopic intervention is required in approximately 10-20% of patients, and surgical intervention is required in less than 1%. The typical clinical presentation of esophageal foreign body ingestion is an acute onset of dysphagia and can be complicated by esophageal perforation, obstruction, aortoesophageal fistula formation, and tracheoesophageal fistula formation. After assessing the primary survey (Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure, IV, O2, monitor) and obtaining the relevant history in suspected foreign body ingestion, the next crucial step in the critical care setting is the physical exam. The exam should include inspection of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, neck, chest, and abdomen, assessing for crepitus, deformities, respiratory distress, or any other signs of complications. Patients with respiratory distress may require intubation before further assessment.

After completing your history and physical exam, identifying what and where the object might be is crucial. Imaging is an essential tool to localize and identify the foreign object and guide management. Plain radiographs are the preferred modality for patients without suspected esophageal obstruction and a history of ingesting blunt, radiopaque, or unknown objects. For those with suspected sharp or pointed foreign body ingestions or those with suspected perforation, a CT neck and chest without contrast is the way to go. Depending on the severity of the patient's symptoms and instability on the initial presentation, imaging may be deferred for emergent Endoscopy. Emergent Endoscopy is indicated in patients with complete esophageal obstruction, disk batteries, or sharp-pointed objects in the esophagus. Regardless, all foreign bodies in the esophagus should be removed via Endoscopy if feasible within 24 hours to avoid complications. While you are ordering the appropriate imaging modalities, it is reasonable to give your fellow ENT surgeon, GI specialist, and/or Cardiothoracic surgeon a call. In perforation or pneumomediastinum, consultants need to evaluate and treat the patient as soon as possible. As you wait for imaging, labs, and ultimately endoscopic removal, it is vital for you to continually reassess the patient to ensure they do not develop signs of esophageal rupture or airway distress. A particular concern also is the suspected proximity of the object to the great vessels of the neck.

Following successful endoscopic retrieval, patients with foreign body ingestion can usually be treated either as outpatients or after a short course of observation. If there is a high risk for complications based on the clinical course or extensive mucosal injury due to the ingestion or the extraction, patients should be hospitalized post endoscopy in the ICU until they are stable enough for the floors. These patients should remain NPO for up to 48 hours, started on IV antibiotics for approximately 7-10 days, and may require follow-up imaging to ensure successful healing. If a foreign body cannot be retrieved endoscopically, and the patient is stable, the object’s passage through the GI tract should be followed with daily radiographs. Surgery is indicated for patients who develop complications, become unstable, or no progression of the foreign body (blunt objects for one week, or sharp objects for three days).

The case continued:

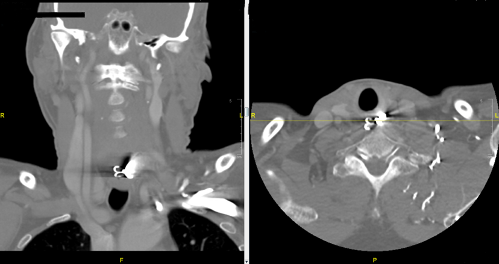

Acting quickly, you assess the patient. He is still not in any acute distress and continues to speak in full, clear sentences without drooling. You do not note any deformities or crepitus on careful palpation of the neck. You do not note any frank blood in his oropharynx, and the rest of his exam is otherwise benign. You decide to call your GI and ENT specialists, who recommend a CT neck and chest. You grab basic labs, including PT/INR, and load the patient up with Zofran and Fentanyl. You do not suspect rupture, and in the absence of fever or leukocytosis you decide to withhold antibiotics. You call the CT scanner to notify them of the patient, and the scan comes back. You take a look:

BOOM! You call both the GI and ENT specialists with the results, who decide to take the patient emergently to the OR for a rigid esophagoscopy with foreign body removal. You continually reassess the patient until they take him back and eventually learn that the operation was successful, and the patient was discharged after several days of monitoring. You sit back down at your desk, sip on your coffee, and prepare to tackle the next case.

References:

1. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Fisher LR, Fukami N, Harrison ME, Jain R, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Maple JT, Sharaf R, Strohmeyer L, Dominitz JA. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Jun;73(6):1085-91. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.010. PMID: 21628009.

2. Khan MA, Hameed A, Choudhry AJ. Management of foreign bodies in the esophagus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004 Apr;14(4):218-20. PMID: 15228825.

3. Lam HC, Woo JK, van Hasselt CA. Management of ingested foreign bodies: a retrospective review of 5240 patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2001 Dec;115(12):954-7. doi: 10.1258/0022215011909756. PMID: 11779322.

4. Wu WT, Chiu CT, Kuo CJ, Lin CJ, Chu YY, Tsou YK, Su MY. Endoscopic management of suspected esophageal foreign body in adults. Dis Esophagus. 2011 Apr;24(3):131-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01116.x. Epub 2010 Oct 13. PMID: 20946132.